Kevin’s Blog/ Sweet and Sour SAGD

SAGD short stories:

Sweet and Sour SAGD

“SAGD short stories” is a blog series about SAGD and process operations.

Natural gas is made up of compounds of hydrogen and carbon, and naturally occurs in oil reservoirs. The SAGD process recovers natural gas along with bitumen, water, and other vapours.

Natural gas is colourless and odourless,

which make leaks hard to detect and increases the chance of exposure.

This was recognized early on as a serious hazard of using natural gas.

To alert people when gas leaks happened, we started adding a smelly, odorant substance to natural gas in the 1800s. This became widespread during the 1900s.

The natural gas component in SAGD fluids produced to the surface doesn’t have any commercial odorant added to it,

but is called either sweet gas or sour gas based on its hydrogen sulphide (H2S) content.

Natural gas containing very little or no H2S is called Sweet Gas.

Alberta defines natural gas containing ≥1% H2S as Sour Gas.

Note: Acid Gas is natural gas containing carbon dioxide (CO2) and H2S.

Sour Gas and Acid Gas are sometimes interchanged because both contain H2S and can smell bad.

While the presence of H2S and CO2 can cause corrosion problems in natural gas piping, the greater hazard is to people exposed to the gas during a leak event.

Exposure to natural gas is serious,

but the hazard of sour gas exposure is of the

highest importance because of the immediate,

acute toxicological effects of breathing

even small amounts of H2S.

H2S gas is a very hazardous chemical asphyxiant, and inhaling H2S interferes with respiration and can be fatal.

H2S gas is colorless, but has specific odour characteristics depending on the concentration.

- At <1 ppm (part per million):

H2S has a very identifiable, rotten egg odour

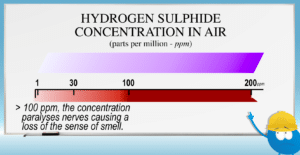

(this is where the “sour” comes from) - From 0 to 30 ppm (approx.):

The rotten egg odour gets stronger - From 30 to 100 ppm (approx.):

The rotten egg odour fades, and the odour becomes sweeter - At >100 ppm (approx.):

H2S paralyses nerves causing a loss of the sense of smell

(This is a critical situation since the smell of gas is our primary personal warning of a contaminated atmosphere. Losing this sense could lead someone to think a contaminated atmosphere is safe and clear of gas.)

At H2S concentrations > 200 ppm, inhaling even a few breaths can cause collapse, respiratory failure, or even death.

In addition to the acute effects, chronic, prolonged exposure to low levels of H2S can also lead to some loss of the sense of smell.

The density of H2S increases its hazard. Heavier than most components in air, H2S will collect in areas with poor ventilation and in Confined Spaces.

And it will accumulate in low areas, even if the low area is outdoors. Over the years, a sad but repeated scenario has played out where one worker is exposed and collapses; followed by a would-be rescuer also being overcome while coming to aid the first downed worker.

This is why the message to workers is:

“If you see someone collapse for no apparent reason,

or see someone unconscious on the ground,

always consider the current conditions

before going to aid the downed person.”

Quickly assess the situation. A person in an odd position on the ground next to a ladder certainly appears to be a fall victim.

But finding a person unconscious after recently hearing a gas warning alarm in the area should make you consider a contaminated atmosphere as a possible factor.

If you think H2S exposure is possible, it’s critical to properly protect yourself before attempting the rescue to prevent being overcome by H2S yourself!

To find out more about the hazards of SAGD operations and H2S,

you can view the Hazards chapter of Contendo’s SAGD Oil Sands Online Course.

Kevin Fox is a senior technical writer at Contendo.

He is a power engineer who has written process education programs for industrial clients since 2009.